There’s snow place like a snow shed

Snow can be a beautiful treat, but anyone who lives with it on a regular basis knows it can also come with many hazards.

Despite their size and power, trains can still fall victim to Mother Nature. BNSF’s predecessor railroads learned the hard way that snowfall could block major lines and avalanches could topple trains without warning. These issues prompted the invention of snow sheds – a simple yet effective solution to big problems.

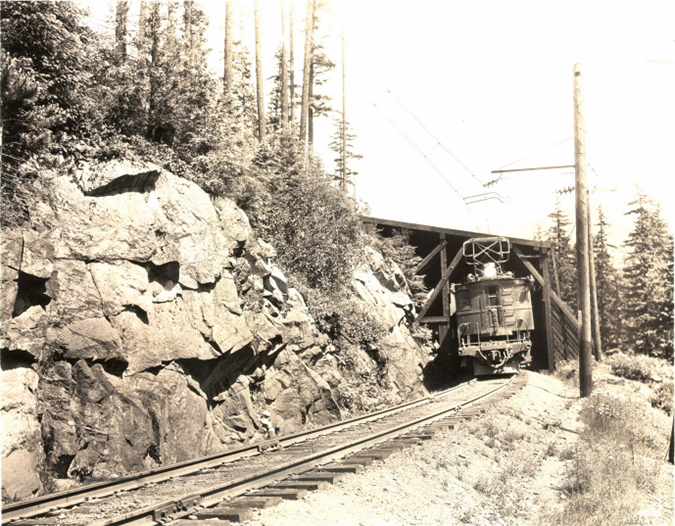

Snow sheds were first created in the late 1800s and became the foundation for sustaining rail transportation in colder regions. They are what they sound like – structures with sloped roofs that deflect snow over the top of long sections of track, sort of like long car ports.

Even with today’s technology, simply diverting snow away from tracks continues to be the most practical solution to nature’s extremes.

“The union between 19th and 21st century technology is fascinating,” said Craig Rasmussen, assistant vice president of Engineering Services and Structures. “Before snow sheds, clearing avalanches meant using picks and shovels. The technology protecting railroads from extreme winters is more than 100 years old, but snow sheds continue to be the physical building block. Each new advancement continues to layer off that.”

BNSF has a total of 17 active snow sheds. Ten of these snow sheds run on the Hi-Line Subdivision in John F. Stevens Canyon near the southern border of Glacier National Park in Montana. The remaining snow sheds are on the Stampede Subdivision through the Cascade Mountains in Washington. The total combined length is more than 6,900 feet.

The Technology Behind Snow Sheds

BNSF’s snow sheds don’t usually cover large areas of the track. As you can see in the image below, avalanches typically occur in the same locations. Like the flow of a river, an avalanche will continue to flow down the same path. It’s not practical to cover all the tracks in its path because the area is too large, so targeting problem spots is still most effective.

Initially, snow sheds were the only way to address high-impact areas. However, as technology advanced, engineers and scientists could analyze and monitor snow conditions, allowing them to predict when and where an avalanche might occur as well as its potential severity.

These technology advances are translated into current, useable data with things like the Railroad Avalanche Danger Scale (RADS), a system that helps engineers predict natural disasters, and a Daisy Bell, a device that blasts sonic waves to trigger controlled avalanches. These help BNSF maintain safe operations by monitoring risks and taking appropriate precautions. For areas that are mostly at risk of heavy snowfall, switch heaters – essentially hot air blowers – keep switches warm, allowing continued safe and efficient operation of trains through snow and ice.

Keeping Snow Sheds Young and Strong

Because most snow sheds are already placed where there’s a pattern of avalanches, BNSF has not had to build a new snow shed in years. The last large project was in Washington around 15 years ago to extend an already existing snow shed. Most snow sheds today have been passed down from predecessors. However, their age doesn’t mean they’re feeble.

BNSF routinely maintains its snow sheds to preserve their strength by addressing the back walls, the roof and the supports.

“Back walls are usually made of concrete to hold back the mountain face, so our crew are repairing cracks or water damage,” explains Rasmussen. “The roof of a snow shed has similar issues to a regular building roof. It doesn’t need to be completely waterproof, but most importantly, engineers make sure it won’t collapse from heavy snow loads.”

“Supports are the hardest to maintain,” he added. “They’re made of wood, so they can decay, and replacing them can be tricky. We usually replace them one by one to keep the structure supported. It’s very surgical.”

Ironically, the biggest threat to snow sheds is fire because they are often near forests, where wildfires are a threat. Because snow sheds are made of wood, they can quickly be damaged. Although responders try to pour water on the snow sheds to prevent them from burning, it’s not always possible to stop the damage.

With the continued improvement of snow technologies and other measures to lessen Mother Nature’s impact, train safety has improved significantly. While there will always be avalanches and heavy snowfall, most of the impacts from these disasters are now preventable. And no matter how technology for handling snow evolves, snow sheds are likely to remain a foundation.